Digital marketing gave us something we'd never had: the ability to track results. This was a godsend for marketers. The more you could test, the faster you improved. Instead of relying on hope and vibes, you could prove your impact with the numbers. This gave marketers more credibility and power in the corporate world, but at a cost.

Numbers. Since teary-eyed arithmetic at the kitchen table, I haven't had a good relationship with them. And now I know why.

The "arithmocracy", Rory Sutherland's term for organizations where the only legitimate language is numbers, has ruined marketing. And we've let them.

You'll often hear "marketing is part art, part science." It's a comforting line, it lets us generalists and social science majors feel like we belong with the well-paid STEM folks, and it acknowledges the messiness of the work.

But let's be honest: marketing isn't a science.

Scientists use precise measurements in controlled environments. Marketers work at the messy intersection of humans, markets, and technology. Scientists have a narrow definition of "right". For marketers, there are many ways to be right and that's a good thing! We don't have to be constrained by the narrow limits of scientific discovery.

Letting data-led strategy dominate has made marketing lazy, boring, and yes — inaccurate. It's time to return to the craft of artful marketing.

As my frustration with data has simmered over the years, many ideas about why have percolated to the top. So, allow me to take down the numbers with my own words.

The Map Is Not The Territory

Maps simplify the territory. That's what makes them useful, they collapse complexity into something you can act on at a glance. But the map is not the thing.

Spreadsheets are maps. They distill thousands of data points into something manageable. But they tell you nothing about how the product worked, how the marketing felt, or what was going through the customer's mind.

A lot of data actually deletes information. Averages flatten many numbers into one. They eliminate the useful behavioral detail each number provides.

You know 97% of visitors didn't convert. You have no idea if they were confused, skeptical, not ready, distracted by their kid, spooked by pricing, whatever. The number tells you what happened and actively obscures why.

Relying on data can make you a lazy analyst of human behavior, which is exactly what you should be doing.

The Measurement Trap

"What gets measured gets managed". (Boy, this quote is instructive about the whole situation.)

Misquoted to Peter Drucker and misunderstood, it led to a scourge of data-led strategy, instead of strategy-led data analysis.

The thinking became: if we can measure it, we should, so we can create a clear picture and hold people accountable. But that's the opposite of what Drucker meant. He was warning about measuring the wrong things and letting metrics distort priorities.

The irony is cutting: relying on data can distort your perception of reality because you undervalue what can't be measured.

Robert McNamara was a numbers man, he built his reputation on statistical rigor at Ford before becoming Secretary of Defense. Rufus Phillips, a former CIA officer, once described how McNamara's management strategy backfired during Vietnam:

McNamara decided that he would draw a chart to determine whether we were winning or not. He was using things like the numbers of weapons recovered, numbers of Viet Cong killed, numbers of Viet Cong defectors. Very statistical.

He asked Edward Lansdale, head of special operations at the Pentagon, to come down. He said, "Look at this."

Lansdale looked, and he said, "There's something missing here."

McNamara said, "What?"

Landsdale said, "The feelings of the Vietnamese people."

You couldn't reduce that to a statistic.

H/T Morgan Housel

Marketing legend Rory Sutherland has a great example, his "Doorman Paradox". In his parable, a management consulting firm sees a hotel doorman's measurable function as "opening the door" and an obvious inefficiency. Their solution is to replace the human expense and liability with an automatic door. Boom, efficiency!

But the doorman's purpose extended far beyond the measurable. His presence created guest safety, status signaling for the hotel, a way to hail cabs, a familiar face for regulars. None of that shows up in a spreadsheet. All of it is felt by the guest.

Do you think Doubletree has a line item for "brand equity gained via cookies"? Or Costco for their $1.50 hot dog? If ice-cold calculation drives your marketing decisions, you'll optimize away the things that people actually care about.

The Causation Problem

Statistics 101: Correlation does not equal causation. But causation is exactly what we're after as marketers. We want to know what leads to results and why.

Much data analysis leaves this alone. First or last click attribution, which many use, ignores the middle part of the process. You could get fancy with position-based or algorithmic attribution, but they all share the same flaw — assigning linear causation to a non-linear process. Human decision-making isn't a funnel, it's a web of impressions, emotions, social proof, timing, and context that no model captures.

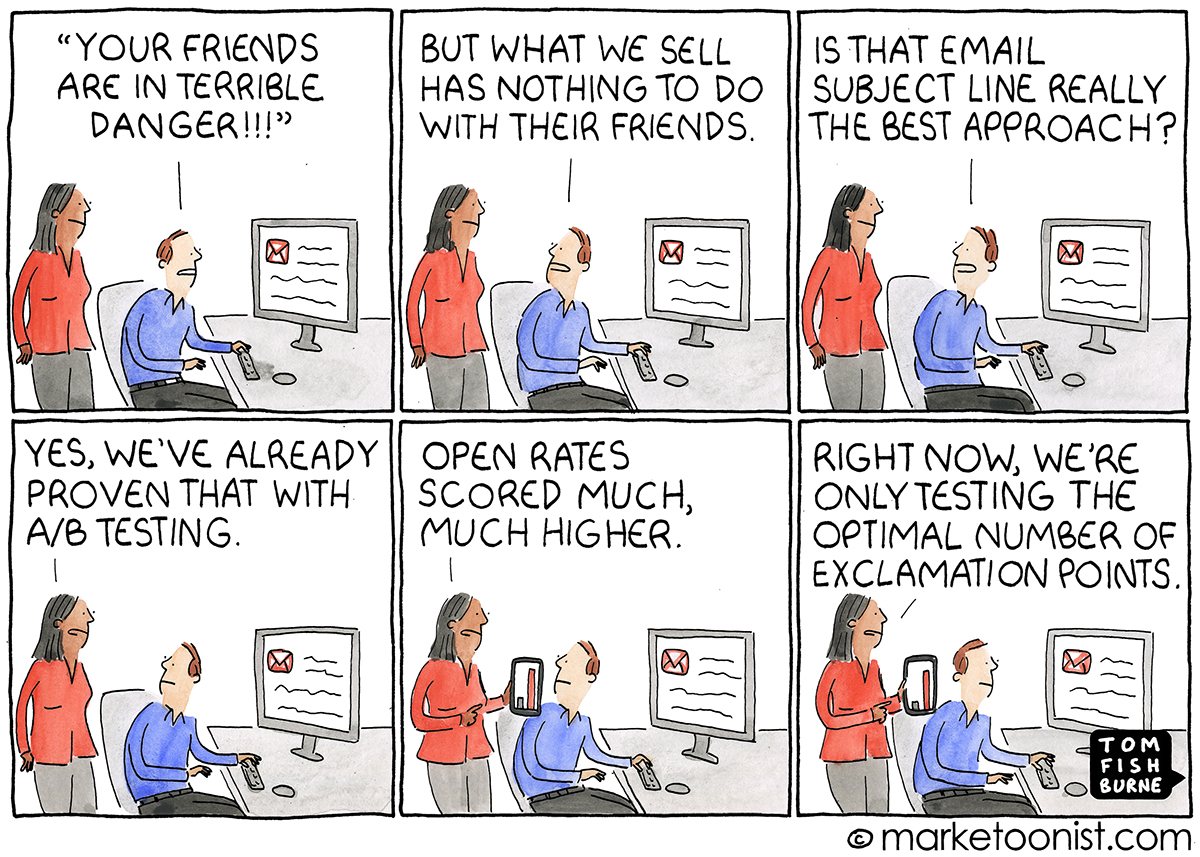

A/B testing is supposed to fix this. "If we have a large enough sample size, we can eliminate confounding factors and discover a clear answer," the thinking goes. It's a nice thought, but ultimately unrealistic.

Two issues. Firstly, most marketers rarely reach adequate sample sizes for statistical significance, declaring winners on limited results. Secondly, A/B tests try to isolate one variable, but the customer doesn't experience your marketing in isolation. The time of day, the length of message, the medium, the mood of the algorithm, that day's news, etc. all have their impacts.

The causation puzzle has three possibilities: X causes Y, Y causes X, or some unknown Z is driving both. In marketing, X, Y, and Z could be almost anything. Any number of things could be affecting your data, and untangling it is far less realistic than we pretend.

Nobody ever got fired for being boring

"Nobody ever got fired for buying from IBM". An outdated quote with a relevant message. Following a safe, established source protects decision makers from risk, even if there is a better alternative.

When the spreadsheet is the judge, everyone defaults to "best practices", whatever's safe, whatever you can defend with the data.

But so much of marketing is earning attention by being different, and establishing differentiation for the brand. This isn't under question, we're wired to pay attention to what stands out to our pattern-seeking brains — the lion emerging from the grass.

Consider the Coinbase Super Bowl Ad in 2022. A bouncing QR code à la the DVD screensavers of our youth. It broke every advertising rule: no copy, no benefits, no CTA, no endorsement, no branding. It also broke Coinbase's website. 445,000 new signups.

There was no data that would've supported this decision. Indeed, that was part of the point. As Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong recalls:

"I guess if there is a lesson here it is that constraints breed creativity, and that as founders you can empower your team to break the rules on marketing because you're not trying to impress your peers at AdWeek or wherever."

The score can lie

Data-driven marketing runs on "resulting". The idea that you should judge the quality of a decision on the quality of its outcome seems obvious and logical. But realizing that a good decision can produce a bad outcome and a bad decision can produce a good one is critical.

A poker player can make the statistically correct call and still lose the hand. That doesn't mean the decision was wrong, it means the outcome was influenced by factors outside their control.

A team sends a discount blast email. Conversions spike. It gets celebrated and repeated. What nobody asked: did those buyers have purchase intent already? Did the discount cannibalize full-price revenue? Did it train your audience to wait for sales? The outcome was good, the decision was bad, and "resulting" ensured it became a "best practice."

There's a deeper problem: marketing offers no counterfactual. You can't know what would have happened if you'd made a different call. Every decision gets exactly one outcome, in one context, with no control group. Resulting isn't a bias you can train yourself out of, it's embedded in the work. Which means the only honest move is to stop treating outcomes as verdicts. Be flexible in your interpretations.

How Your Dashboard Destroys Your Brand

Most data analysis looks backward, one campaign at a time. Management pressures you to improve numbers "on this campaign" or "this quarter", and so you resort to cheap tactics to juice engagement.

Most of what marketing should be is long-term brand building. Stacking awareness, proof, and trust over time so that when customers are ready — they buy from you.

Relying on data creates a form of audience capture. Like most data-driven instincts, it feels rational but pulls you in the wrong direction. When you optimize for what your data tells you, you create a feedback loop that drags you away from your vision and toward simply performing for your audience. It feels like listening. In practice, it's creative decay.

Here's how it goes:

- You post a thoughtful industry analysis: modest engagement, doesn't stand out in the data.

- You post a meme or hot take: numbers spike, it gets encouraged as good idea.

- Suddenly, your B2B business sounds more like a teenager than a thought leader.

- Engagement goes up, but trust goes down. One is measurable, one isn't.

Even in the modest case, it makes you sound like everyone else:

- You build a distinctive point of view with long form articles.

- Engagement data and best practices says, "shorter, punchier listicles".

- A year later, you sound like every other blog and you've lost your valuable differentiation.

But even if you avoid Audience Capture, your dashboard hides another trap: Goodhart's Law. "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure." The moment you make a measurement a goal, people optimize for the metric instead of the thing it was meant to represent.

When the British colonial government offered bounties for cobra heads in Delhi, locals started breeding cobras. The metric went up. The problem got worse. The same thing happens every time a marketing team makes something like "time on page" as a target. The idea is for people to find content valuable, in practice it leads to bloated pages.

There's a deeper problem underneath all of this. All data has one thing in common: it comes from the past. Every decision you need to make is about the future. Kierkegaard put it well: life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.

Marketing is the same. You can analyze what happened endlessly, but at some point you have to make a judgment call about what comes next, and you shouldn't let a spreadsheet make that call for you.

Return to the Craft

I know what many of you are thinking right now. "If not data, then what?" You've been brow beaten and trained by managers to prove everything with a spreadsheet. Everyone's LinkedIn headline pressures you to do the same.

I'm not saying abandon data. It's a useful lens, it lets us see patterns we'd otherwise miss. But it is not a single source of truth, and letting it drive our decisions has produced tepid, undifferentiated marketing.

You have to let go, and focus on what you can control. Robert Greene put it sharply: "The need for certainty is the greatest disease the mind faces." Data feels like certainty. That's exactly why it's dangerous.

You don't control the algorithm, the platform, the culture, or the customer's thumb. You do control your thinking, your craft, and your standards. Focus there. Establish a clear vision for your brand, chisel away at the product, and stop letting a dashboard overrule your judgment.

This requires faith that good work compounds, even when the results don't show it immediately.

John Kennedy Toole wrote A Confederacy of Dunces and it was rejected by every publisher he brought it to. After his death, his mother discovered the manuscript and continued pushing its publication. A single editor took it on, and it later won the Pulitzer.

Think about that. What changed about the writing? Nothing. Only the circumstances changed. If you only judge a piece of work by its results, you're leaving so much on the table.

We need to return to long term, intentional brand building. Let sales be responsible for short-term results. Marketing's job is to ensure sales still has a job in three years.

Everyone in marketing is fighting for a competitive advantage. Here's one: while everyone else is focused on being data-driven and results-oriented, you can be human-driven and craft-focused.

What does this look like in practice? Here's where to start.

Reaffirm your process and standards. Ideas are only as valuable as their execution. To move away from reactive, data-led marketing, you need a process that protects the creative work. Establish clear standards for what goes out the door, and prioritize quality over quantity. Give your team the psychological safety to ignore short-term noise and produce work drives long-term value and team pride.

Cultivate taste. Taste is the unquantifiable moat that separates beloved brands from cookie-cutter competitors. To build it, step out of your analytical mind and start gathering inspiration from architecture, entertainment, fashion, or nature. Create a swipe file and have your team add to it. Then, evaluate your marketing (yours or a competitor's) simply as a human. What catches your eye? What gives you pause? What actually motivates or demotivates you? Use those answers to bring humanity back to your work.

Lead with conviction. Marketers use data as both a crutch and a shield. When searching for ideas, they default to the dashboard. When a campaign fails, they shrug and say they were just following the numbers. This lack of accountability has created a sea of watered-down content. Cultivating taste gives you the courage to stand firmly behind your point of view, even when the short-term metrics don't immediately support it.

Starve the dashboard. I'm not anti-data. I'm anti-data worship. The antidote to the flaws described above is to drastically reduce your data diet. Choose one (maybe two) north-star metrics that truly reflect the health of your brand, and commit to checking them quarterly. By intentionally starving the dashboard, you force yourself to trust your intuition instead of leaning on a spreadsheet to inform every decision.